Nothing worth seeing here

What do non-Indigenous Australians know about the mythological power of Aboriginal standing stone arrangements? Not much it would seem.

So little that a bunch of Celts in NSW could in the late-1990s brazenly lay claim to, and be granted by the National Trust, Australian standing stone heritage status as a National Monument for their faux Stonehenge circle consisting of 38 ‘menhirs’, erected circa 1991. At their inauguration, the Governor of New South Wales, His Excellency Rear Admiral Peter Sinclair, AO, declared: “The standing stones would link with structures on the other side of the world, which go back thousands of years…” No reference was made of linking to their Indigenous Australian antecedents, whose culture goes way back further – at last count 65,000 years.

Yet artificially wedged vertical shards of rock were once placed throughout the continent by the First Australians. They formed circles for ceremony; acted as signifiers for sacred places; represented dangerous ancestor beings of malign power; or stood at attention in sculptural lines forming the shape of the most powerful spiritual creators who emerged during the Dreaming. Typically, few of the white newcomers displayed the slightest interest in what such standing stones meant. Many were knocked over as heathen artefacts or simply ignored, falling victim to careless cattle or time and entropy.

So little that a bunch of Celts in NSW could in the late-1990s brazenly lay claim to, and be granted by the National Trust, Australian standing stone heritage status as a National Monument for their faux Stonehenge circle consisting of 38 ‘menhirs’, erected circa 1991. At their inauguration, the Governor of New South Wales, His Excellency Rear Admiral Peter Sinclair, AO, declared: “The standing stones would link with structures on the other side of the world, which go back thousands of years…” No reference was made of linking to their Indigenous Australian antecedents, whose culture goes way back further – at last count 65,000 years.

Yet artificially wedged vertical shards of rock were once placed throughout the continent by the First Australians. They formed circles for ceremony; acted as signifiers for sacred places; represented dangerous ancestor beings of malign power; or stood at attention in sculptural lines forming the shape of the most powerful spiritual creators who emerged during the Dreaming. Typically, few of the white newcomers displayed the slightest interest in what such standing stones meant. Many were knocked over as heathen artefacts or simply ignored, falling victim to careless cattle or time and entropy.

Last dry season, I was bushwalking with friends and family in remote gorge country on the Kimberley coast when we came across four sets of thin, sharp-edged standing stone shards on tops of waterfalls, clearly artificially placed. We had walked in the Kimberley before, as well as the Arnhem Land plateau, and none of us, including our experienced guide, had ever seen these wedged, vertical sandstone slabs, so startlingly at-odds with their surrounds. Particularly impressive was a large standing stone circle next to a towering waterfall with commanding views.

We had set off down the Roe River in the Prince Regent National Park, camping next to pools below waterfalls that regularly punctuated our progress. At every waterfall, rock art shelters crowded with ancestral beings and creation stories overlooked the dark, deep green of secret/sacred pools. Among them were the lively slim-limbed figures of truly ancient, pre-Ice Age Gwion Gwion rock art, of which, like the standing stone arrangements, little is known.

Unsurprisingly, that didn’t stop Victoria’s Royal Geographical Society in 1891 from appropriating this other worldly 15,000 year-plus distinctive rock art form in honour of their ‘discoverer’, Ballarat pastoralist Joseph Bradshaw. Just another small step in the repeating pattern of continental renaming that had started with Captain Cook and has stretched above and beyond the Celts of Glen Innes.

Joseph was embarked on a stupendous folly when he serendipitously stumbled across his eponymous rock art panels. He was misguidedly seeking fresh pasture for his central Victorian sheep among the rocky gorges and the extreme wet/dry weather cycle of the Kimberley. It was never going to work. Still, Joseph was the first white man in the region and the culture he represented now fully occupied the top stratum of history. To paraphrase Black Lives Matter leader, DeRay Mckesson, in colonising the world, white privilege assumes that only white lives matter.

We had set off down the Roe River in the Prince Regent National Park, camping next to pools below waterfalls that regularly punctuated our progress. At every waterfall, rock art shelters crowded with ancestral beings and creation stories overlooked the dark, deep green of secret/sacred pools. Among them were the lively slim-limbed figures of truly ancient, pre-Ice Age Gwion Gwion rock art, of which, like the standing stone arrangements, little is known.

Unsurprisingly, that didn’t stop Victoria’s Royal Geographical Society in 1891 from appropriating this other worldly 15,000 year-plus distinctive rock art form in honour of their ‘discoverer’, Ballarat pastoralist Joseph Bradshaw. Just another small step in the repeating pattern of continental renaming that had started with Captain Cook and has stretched above and beyond the Celts of Glen Innes.

Joseph was embarked on a stupendous folly when he serendipitously stumbled across his eponymous rock art panels. He was misguidedly seeking fresh pasture for his central Victorian sheep among the rocky gorges and the extreme wet/dry weather cycle of the Kimberley. It was never going to work. Still, Joseph was the first white man in the region and the culture he represented now fully occupied the top stratum of history. To paraphrase Black Lives Matter leader, DeRay Mckesson, in colonising the world, white privilege assumes that only white lives matter.

Two upright shards guarded the first large circle of stones, hidden some 100 metres inland from the towering waterfall. On a levelled plateau, the standing stones ringed a knoll, perfect for viewing whatever ceremonies or dances were performed around its perimeter. Even the most hardened sceptic among us felt that the ring of jagged shards once held power and authority.

We remembered that a lone Aboriginal-grafted ghost gum had stood guard on a blood red clifftop as we entered the narrow gorge: its white branch tied back in an O framing a vivid blue sky. We could only speculate.

Curiosity piqued, on returning to Melbourne, I went to the State Library and spied in the catalogue a book titled The History of Australian Standing Stones. Aha, I thought… but was soon deflated on opening its pages. With unintended irony, this history of Australian standing stones focuses solely on a newly minted Celtic stone circle of three metre high monumental stones established at Glenn Innes in New England, not even 30 years old. Incredibly, just seven years post-erection, the NSW National Trust declared this Celtic copy “a significant place of Australian heritage.” Visitors will “feel an aura of power among their majestic presences,” writes the standing stones’ historian, John Mathews.

All that The History of Australian Standing Stones has to say about the tens of millenia-long Indigenous Ngoorabul heritage of the region is contained in one cursory sentence: they were migratory, only visiting seasonally. It’s a common trope: as though the Ngoorabul people were never really there; that they left no mark. As a final unintended insult, the Glenn Innes Celts asked the local Aboriginal land council if they could appropriate a bunyip as the mascot for their stone circle. The land council said no, so the Celts settled on the idea of a mascot dinosaur, which they named Gleniss.

An online search of archaeological field surveys in New England did actually manage to turn up some Aboriginal standing stone arrangements found there in the 1970s. But there was no attempt at contextual analysis; they are simply listed without comment.

The State Library also held one Australian Archaeology 2012 journal article on a survey of 32 standing stone sites in Jawoyn country, north-east of Katherine in the NT. This, however, could cast little light on their purpose other than they were “signifiers,” possibly of major rock art sites.

We remembered that a lone Aboriginal-grafted ghost gum had stood guard on a blood red clifftop as we entered the narrow gorge: its white branch tied back in an O framing a vivid blue sky. We could only speculate.

Curiosity piqued, on returning to Melbourne, I went to the State Library and spied in the catalogue a book titled The History of Australian Standing Stones. Aha, I thought… but was soon deflated on opening its pages. With unintended irony, this history of Australian standing stones focuses solely on a newly minted Celtic stone circle of three metre high monumental stones established at Glenn Innes in New England, not even 30 years old. Incredibly, just seven years post-erection, the NSW National Trust declared this Celtic copy “a significant place of Australian heritage.” Visitors will “feel an aura of power among their majestic presences,” writes the standing stones’ historian, John Mathews.

All that The History of Australian Standing Stones has to say about the tens of millenia-long Indigenous Ngoorabul heritage of the region is contained in one cursory sentence: they were migratory, only visiting seasonally. It’s a common trope: as though the Ngoorabul people were never really there; that they left no mark. As a final unintended insult, the Glenn Innes Celts asked the local Aboriginal land council if they could appropriate a bunyip as the mascot for their stone circle. The land council said no, so the Celts settled on the idea of a mascot dinosaur, which they named Gleniss.

An online search of archaeological field surveys in New England did actually manage to turn up some Aboriginal standing stone arrangements found there in the 1970s. But there was no attempt at contextual analysis; they are simply listed without comment.

The State Library also held one Australian Archaeology 2012 journal article on a survey of 32 standing stone sites in Jawoyn country, north-east of Katherine in the NT. This, however, could cast little light on their purpose other than they were “signifiers,” possibly of major rock art sites.

I remembered that archaeologist Professor Ian McNiven had taken part in surveys of some of the fabulous vaulted rock art galleries in Jawoyn country. I emailed and asked what he knew about standing stones. Not much, he said, and sent me a few academic journal articles by archaeologists on the subject. While they were confirmed as once being found throughout Australia, they are only physically described and enumerated. The authors speculate that two major types occurred – either forming ceremonial sites representing creation stories from the Dreaming or as markers for sacred places.

In an Australian Archaeology 2018 journal article on standing stones in Far North Queensland, Professor McNiven and other authors conclude: “Despite their ubiquity, stone arrangements are an understudied site type with their distribution and morphological variability remaining poorly documented and their functional variability poorly understood.”

Little was known about their specific purpose, other than they “have high significance values to Indigenous Australians and are usually associated with… socio-religious beliefs and ceremonial/ritual activities.”

In an Australian Archaeology 2018 journal article on standing stones in Far North Queensland, Professor McNiven and other authors conclude: “Despite their ubiquity, stone arrangements are an understudied site type with their distribution and morphological variability remaining poorly documented and their functional variability poorly understood.”

Little was known about their specific purpose, other than they “have high significance values to Indigenous Australians and are usually associated with… socio-religious beliefs and ceremonial/ritual activities.”

At a traditional Aboriginal-style mosaic burning in autumn this year, I met a softly spoken cultural anthropologist, Jim Birckhead, who had recently carried out heritage-funded desktop research on standing stones in the Pilbara and Kimberley. He remarked that without deep cultural understanding of the rationale for the stones’ arrangement, any attempt at speculating about their purpose (maybe it was a practical use, like a bird hide?) or their spiritual meaning (maybe it represents an ancestor creation being?) needs to be resisted. Without talking to a knowledgeable elder in the presence of the standing stones, they will remain just that – a lithic line, limited to an existence devoid of meaning on an archaeological list.

It’s not generally recognised, but even ‘cultural burnings’, as they’ve become known, are underpinned by a socio/religious aspect. Jim and I were among 30 people brought together by the Wooragee Landcare group to light up a patch of grass and weeds in the open box woodland of north-east Victoria under the steady gaze of ‘Uncle Rod’ Mason, a Ngarigo elder. While growing up in the Western Desert, he had gained a responsibility, along with everyone else in his language group, learning through experience when and how to deploy fire. Where Western culture breeds fear of fire, Rod relished it as an agent of renewal: “You got to fire it! When you burn Country, it makes it brand new fresh.”

I asked him what he saw as the cultural essence of Aboriginal-style burning. “Cultural fire is gender-based,” he answered without hesitation. “Man or woman, we had our own secrets. Woman looked after soft soil with herbs and grasses. Men cared for tall trees like stringybarks or ironbarks. Kids had a role crunching up kangaroo dung – it’s key to slow burning along with plants and trees to make charcoal, the magic ingredient for life springing up fresh.”

Wind, fire and rain – these are the “three Laws” of Indigenous fire management continent-wide, said Uncle Rod. Ideally, you would have representatives from all three totem groups present when making fire. “You have [for example] to get waterbird and eagle totems working together.”

The complexities of the clan relationships that underly slow-burn, mosaic pattern work are yet to surface in the mainstream. Following Uncle Rod’s lead was counter-intuitive enough for most of us. He instructed us to remove logs and large sticks from the patch to be burnt, reducing the fuel load. Next, he tested the wind and had us light a spread of tiny fires burning backwards up the slope. We had to move around the edges of the patch, beating out any fire that crossed its boundaries. It was a wonderfully gentle process, accompanied by much laughter, chatter and no fear.

Captain Cook admired 250 years ago what the settlers only saw as threat. Near his namesake town in north Queensland, he records how the Guueu Yimithirr people “produce fire with great facility, and spread it in a wonderful manner… and we imagined that these fires were intended in some way for the taking of the kangaroo…” But neither he nor those who followed could rise to imagine that Aboriginal mosaic burning patterned the entire continent, as vital and connected as the scales on a crocodile’s back or the feathers on an eagle’s wing.

It’s not generally recognised, but even ‘cultural burnings’, as they’ve become known, are underpinned by a socio/religious aspect. Jim and I were among 30 people brought together by the Wooragee Landcare group to light up a patch of grass and weeds in the open box woodland of north-east Victoria under the steady gaze of ‘Uncle Rod’ Mason, a Ngarigo elder. While growing up in the Western Desert, he had gained a responsibility, along with everyone else in his language group, learning through experience when and how to deploy fire. Where Western culture breeds fear of fire, Rod relished it as an agent of renewal: “You got to fire it! When you burn Country, it makes it brand new fresh.”

I asked him what he saw as the cultural essence of Aboriginal-style burning. “Cultural fire is gender-based,” he answered without hesitation. “Man or woman, we had our own secrets. Woman looked after soft soil with herbs and grasses. Men cared for tall trees like stringybarks or ironbarks. Kids had a role crunching up kangaroo dung – it’s key to slow burning along with plants and trees to make charcoal, the magic ingredient for life springing up fresh.”

Wind, fire and rain – these are the “three Laws” of Indigenous fire management continent-wide, said Uncle Rod. Ideally, you would have representatives from all three totem groups present when making fire. “You have [for example] to get waterbird and eagle totems working together.”

The complexities of the clan relationships that underly slow-burn, mosaic pattern work are yet to surface in the mainstream. Following Uncle Rod’s lead was counter-intuitive enough for most of us. He instructed us to remove logs and large sticks from the patch to be burnt, reducing the fuel load. Next, he tested the wind and had us light a spread of tiny fires burning backwards up the slope. We had to move around the edges of the patch, beating out any fire that crossed its boundaries. It was a wonderfully gentle process, accompanied by much laughter, chatter and no fear.

Captain Cook admired 250 years ago what the settlers only saw as threat. Near his namesake town in north Queensland, he records how the Guueu Yimithirr people “produce fire with great facility, and spread it in a wonderful manner… and we imagined that these fires were intended in some way for the taking of the kangaroo…” But neither he nor those who followed could rise to imagine that Aboriginal mosaic burning patterned the entire continent, as vital and connected as the scales on a crocodile’s back or the feathers on an eagle’s wing.

Jim Birckhead.

Jim Birckhead.

After the Wooragee cultural burning, I contacted Dr Birckhead who sent me a copy of his desktop research carried out with archaeologist, Phil Czerwinski, on past studies into the significance and meaning of Indigenous standing stone arrangements in the Pilbara and the Kimberley. Such arrangements, they found, display a wide range of characteristics from individual markers as a ‘memorial’ to a significant event; to long lines leading to an initiation site; stones forming the shape of an ancestral being; to a circle around a central hollow acting as a fertility ‘increase’ site for a particular plant or animal; or in defining a place of ceremonial worship.

Stone circles such as we encountered in the Kimberley are likely to have had a ceremonial purpose within an overarching creation story. Individual slabs might represent creator beings from the Dreaming who have metamorphosed into stone. Sometimes they were “venerated by men who regard the rocks as patrilineal ancestors,” said Dr Birckhead.

Dr Birckhead commented that mythological and fertility increase sites “are often entwined.” After all, a major reason for singing and dancing in ceremony is to animate a particular totem plant or animal, boosting its breeding potency.

To cite an example from the report on a totemic ‘increase’ site. Two stone arrangements at a Western Desert site consist, first, of 30 small piles of stone, with a line of stones leading to two upright stones embedded in the claypan. The second arrangement consists of a large heap of stones surrounded by small piles of stones.

What does it mean? In 1974, two archaeologists visited the site with Aboriginal informants. They described the first stone arrangement as representing a woman preparing damper from the seed of a Kurumi plant for the people camped beyond the windbreak. A man (the larger of the two isolated stones) is helping with the chore. After enjoying this meal, the men move across to the second arrangement where they perform a fertility increase ceremony. The large heap of stones at the second site is said to represent a group of dancers, surrounded by campfires.

What would seem immediately clear is that without the context provided by the Aboriginal informants, the stones have nothing to say. First-hand involvement with Indigenous elders is vital, says Dr Birckhead, given that the stones “defy interpretation by inspection.”

Stone circles such as we encountered in the Kimberley are likely to have had a ceremonial purpose within an overarching creation story. Individual slabs might represent creator beings from the Dreaming who have metamorphosed into stone. Sometimes they were “venerated by men who regard the rocks as patrilineal ancestors,” said Dr Birckhead.

Dr Birckhead commented that mythological and fertility increase sites “are often entwined.” After all, a major reason for singing and dancing in ceremony is to animate a particular totem plant or animal, boosting its breeding potency.

To cite an example from the report on a totemic ‘increase’ site. Two stone arrangements at a Western Desert site consist, first, of 30 small piles of stone, with a line of stones leading to two upright stones embedded in the claypan. The second arrangement consists of a large heap of stones surrounded by small piles of stones.

What does it mean? In 1974, two archaeologists visited the site with Aboriginal informants. They described the first stone arrangement as representing a woman preparing damper from the seed of a Kurumi plant for the people camped beyond the windbreak. A man (the larger of the two isolated stones) is helping with the chore. After enjoying this meal, the men move across to the second arrangement where they perform a fertility increase ceremony. The large heap of stones at the second site is said to represent a group of dancers, surrounded by campfires.

What would seem immediately clear is that without the context provided by the Aboriginal informants, the stones have nothing to say. First-hand involvement with Indigenous elders is vital, says Dr Birckhead, given that the stones “defy interpretation by inspection.”

Winter came and I had a long-standing booking to swim with whale sharks at Ningaloo Reef and embark on what was to prove a White Man’s Dreaming circuit around the Pilbara. When I examined a map, the Burrup Peninsula looked near Ningaloo (in tyranny of distance terms), and I recalled that Birckhead’s and Czerwinski’s report had mentioned that the Burrup possessed 130 standing stone arrangements. I knew it was renowned for having the world’s largest outdoor galleries of rock art – more than one million engraved figurative images. It seemed too good a coincidence not to add a tour of these most ancient of petroglyphs as the finale of our Pilbara circuit.

It was mid-July, the tail end of the coral spawning that attracts these gentle giants to Ningaloo Reef; foraging out beyond the churning white tops rolling along the reef’s fringe. Early one morning, we queued with hundreds of other tourists on a bleak jetty while cheery young females checked our names and details, then ferried us out on zodiacs to an arc of sleek whale-watching cruisers. We shadowed the whale sharks as they proceeded in stately procession up and down the far side of the reef. Manoeuvred into position by our crew, we would line up across the stern in flippers and snorkels, tensing to leap again and again into the ocean deep on the command, “Go, go, go!”

Mission accomplished, we entered the White Man’s Dreaming circuit driving in convoy with other 4WD rigs, caravans and elaborate camper trailer ‘set ups’ through a landscape littered with names and stories harking back a mere one hundred years or so. As is true for most of Australia, Western celebration in the Pilbara of heroic stockmen, military exploits and rugged miners has undone and unsung the original Australians’ signposts and culture. What worse an example exists than the fate that befell the region’s second highest peak? Looming above the mining town of Tom Price, its builders in 1965 ignored the Indigenous locals and bestowed the banal name of Mt Nameless on what the Yinhawangka people called Jarndunmunha.

It was mid-July, the tail end of the coral spawning that attracts these gentle giants to Ningaloo Reef; foraging out beyond the churning white tops rolling along the reef’s fringe. Early one morning, we queued with hundreds of other tourists on a bleak jetty while cheery young females checked our names and details, then ferried us out on zodiacs to an arc of sleek whale-watching cruisers. We shadowed the whale sharks as they proceeded in stately procession up and down the far side of the reef. Manoeuvred into position by our crew, we would line up across the stern in flippers and snorkels, tensing to leap again and again into the ocean deep on the command, “Go, go, go!”

Mission accomplished, we entered the White Man’s Dreaming circuit driving in convoy with other 4WD rigs, caravans and elaborate camper trailer ‘set ups’ through a landscape littered with names and stories harking back a mere one hundred years or so. As is true for most of Australia, Western celebration in the Pilbara of heroic stockmen, military exploits and rugged miners has undone and unsung the original Australians’ signposts and culture. What worse an example exists than the fate that befell the region’s second highest peak? Looming above the mining town of Tom Price, its builders in 1965 ignored the Indigenous locals and bestowed the banal name of Mt Nameless on what the Yinhawangka people called Jarndunmunha.

Gary Slee with the Pluto gas plant flaring behind.

Gary Slee with the Pluto gas plant flaring behind.

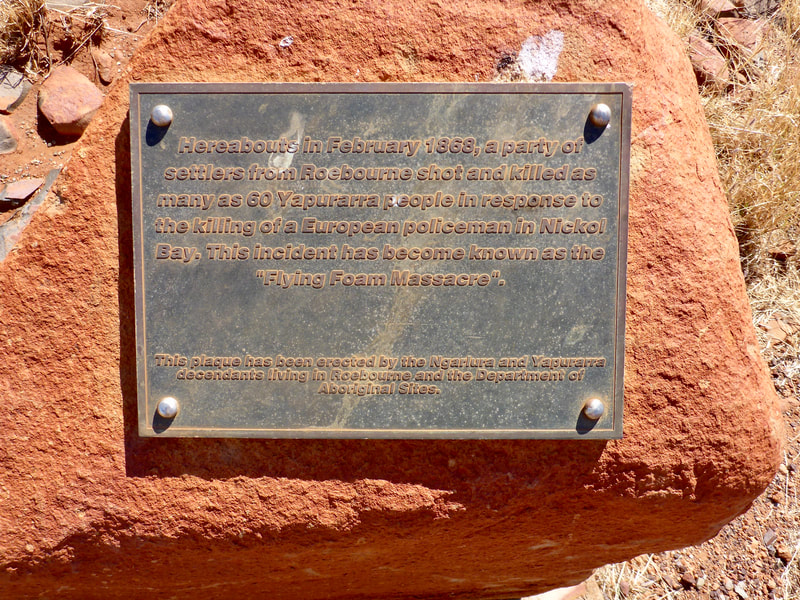

Overlooking King Bay on the Burrup Peninsula, a small brass plaque commemorates one of Australia’s worst frontier massacres. In 1868, a group of Yaburara men set a chained comrade free, then killed his sleeping police captor and two assistants. These three deaths resulted in spiralling payback where, over the period of one week, sworn in ‘special constables’ led by two wealthy settlers hunted down and shot 60 men, women and children – usually in the back as they fled capture.

The killings began with an ambush in King Bay, followed by the vigilantes pursuing the Yaburara as they tried to hide in the peninsula’s hills and the nearby islands of the Dampier Archipelago. None of the alleged Yaburara ‘murderers’ were apprehended. This was to justify the killing spree continuing for another three months. When next to no Yaburara were left, the government superintendent was “glad” to inform his superiors that the “natives” were now “quiet.”

Overall, an estimated 150 Yaburara were massacred. Practically all those artists and custodians who lived among their artworks on the peninsula they called Murujuga were wiped out in 1868.

Today, the largest collection of standing stones on Murujuga bristles like a castle rampart on the hilltop overlooking the memorial plaque and the still waters of King Bay. Of the original 138 counted, by 2004 only 40 were still standing undamaged. Vandals had pushed over or sawn off tops as though they knew the few Yaburara survivors had erected the standing stones as gravestones in memory of those massacred. But, in truth, we don’t know when they were erected or what they signify. The voices of those who placed them were silenced within five years of settlers arriving.

In the Deep Creek car park, directly opposite the world’s largest ammonium nitrate plant, we met our guide Gary Slee from Friends of Australian Rock Art (FARA). Ahead of us in Deep Creek gorge, rose the tumbled hillocks of uniquely baked, 2.9 billion year-old red rock rubble. A passionate FARA volunteer with over 40 years acquired knowledge, Gary pointed out art treasures dating back over 40,000 years pecked or painstakingly etched onto flat, super hard rock slabs. Some that stick in my mind were the extinct animals like the fat-tailed kangaroo with spots and the ‘increase’ site for thylacine, last sighted on the northern mainland over 4,000 years ago. And the etching of a three rigged sailing ship, probably the buccaneer Dampier’s as he passed the peninsula some 320 years ago. A visiting BBC journalist and British merchant navy veteran was astonished, claiming it is illustratively correct. Gary’s favourites are the intricate round-eyed masked faces, dating back to the earliest phase of artwork.

On the other side of King Bay from the memorial plaque lies oil giant Woodside’s supply base. Conveniently vacant of custodians and Native Title claimants, the Burrup’s seemingly ‘empty’ rubble of rocks was seen as ideally located for industrial purposes when vast undersea gas reserves were discovered beneath the North West Shelf in 1971.

Woodside cast aside Murujuga and named the peninsula after Henry Burrup, a bank clerk murdered in an armed robbery. Industrial development now includes Woodside’s massive Pluto natural gas processing plant; two of Rio Tinto’s iron ore ports; Dampier Salts crystalliser ponds and port; and the potentially explosive ammonia plant that has a 1.7 kilometre exclusion zone.

Ironically, it was only as industrial development encroached that the extent and sequence of the Yaburara’s unique rock art came ever sharper into focus. ‘Industry and conservation can work together harmoniously’ is the mantra that the government/industry/tourist & media complex continue to roll out as more and more industry creeps incrementally along Murujuga’s edges.

“Yet, the demands of industry still take precedence over the preservation of the petroglyphs,” remarks Gary Slee. Standing on a hillside in Murujuga, he gestured towards the orange-flaring stacks of the Pluto gas plant, omnipresently visible and roaring: “They produce among the highest carbon emissions of any industrial development in the southern hemisphere, and tests show they are causing acid rain eroding the artwork. Although the technology exists to upgrade, Woodside has ignored our pleas.”

The cost of reducing emissions is estimated at two percent of Woodside’s annual profits. It’s not a priority.

We continue, as historian Mark McKenna asserts, with “the struggle to truly ‘see’ Indigenous cultural heritage as worthy of the same protection as non-Indigenous heritage. Our failure to see is rooted in a long history of prejudice that we have yet to fully overcome.”

The killings began with an ambush in King Bay, followed by the vigilantes pursuing the Yaburara as they tried to hide in the peninsula’s hills and the nearby islands of the Dampier Archipelago. None of the alleged Yaburara ‘murderers’ were apprehended. This was to justify the killing spree continuing for another three months. When next to no Yaburara were left, the government superintendent was “glad” to inform his superiors that the “natives” were now “quiet.”

Overall, an estimated 150 Yaburara were massacred. Practically all those artists and custodians who lived among their artworks on the peninsula they called Murujuga were wiped out in 1868.

Today, the largest collection of standing stones on Murujuga bristles like a castle rampart on the hilltop overlooking the memorial plaque and the still waters of King Bay. Of the original 138 counted, by 2004 only 40 were still standing undamaged. Vandals had pushed over or sawn off tops as though they knew the few Yaburara survivors had erected the standing stones as gravestones in memory of those massacred. But, in truth, we don’t know when they were erected or what they signify. The voices of those who placed them were silenced within five years of settlers arriving.

In the Deep Creek car park, directly opposite the world’s largest ammonium nitrate plant, we met our guide Gary Slee from Friends of Australian Rock Art (FARA). Ahead of us in Deep Creek gorge, rose the tumbled hillocks of uniquely baked, 2.9 billion year-old red rock rubble. A passionate FARA volunteer with over 40 years acquired knowledge, Gary pointed out art treasures dating back over 40,000 years pecked or painstakingly etched onto flat, super hard rock slabs. Some that stick in my mind were the extinct animals like the fat-tailed kangaroo with spots and the ‘increase’ site for thylacine, last sighted on the northern mainland over 4,000 years ago. And the etching of a three rigged sailing ship, probably the buccaneer Dampier’s as he passed the peninsula some 320 years ago. A visiting BBC journalist and British merchant navy veteran was astonished, claiming it is illustratively correct. Gary’s favourites are the intricate round-eyed masked faces, dating back to the earliest phase of artwork.

On the other side of King Bay from the memorial plaque lies oil giant Woodside’s supply base. Conveniently vacant of custodians and Native Title claimants, the Burrup’s seemingly ‘empty’ rubble of rocks was seen as ideally located for industrial purposes when vast undersea gas reserves were discovered beneath the North West Shelf in 1971.

Woodside cast aside Murujuga and named the peninsula after Henry Burrup, a bank clerk murdered in an armed robbery. Industrial development now includes Woodside’s massive Pluto natural gas processing plant; two of Rio Tinto’s iron ore ports; Dampier Salts crystalliser ponds and port; and the potentially explosive ammonia plant that has a 1.7 kilometre exclusion zone.

Ironically, it was only as industrial development encroached that the extent and sequence of the Yaburara’s unique rock art came ever sharper into focus. ‘Industry and conservation can work together harmoniously’ is the mantra that the government/industry/tourist & media complex continue to roll out as more and more industry creeps incrementally along Murujuga’s edges.

“Yet, the demands of industry still take precedence over the preservation of the petroglyphs,” remarks Gary Slee. Standing on a hillside in Murujuga, he gestured towards the orange-flaring stacks of the Pluto gas plant, omnipresently visible and roaring: “They produce among the highest carbon emissions of any industrial development in the southern hemisphere, and tests show they are causing acid rain eroding the artwork. Although the technology exists to upgrade, Woodside has ignored our pleas.”

The cost of reducing emissions is estimated at two percent of Woodside’s annual profits. It’s not a priority.

We continue, as historian Mark McKenna asserts, with “the struggle to truly ‘see’ Indigenous cultural heritage as worthy of the same protection as non-Indigenous heritage. Our failure to see is rooted in a long history of prejudice that we have yet to fully overcome.”

Birckhead’s and Czerwinski’s report concludes that “stone arrangements are one of the least understood Aboriginal cultural features” and further study is required.

Knowledgeable elders still exist, says Dr Birckhead. “The old people I worked with have all been through the Law and know their part of the songlines and Dreaming tracts well. They sing these relationships in language, which is hard for non-initiated people to grasp.”

Living in towns on the coast, the elders seldom get back to Country. Substantial investment is required for extensive site visits, involving archaeologists and anthropologists, accompanied by cultural liaison officers as interpreters. Otherwise, each site’s totemic affiliations and creation stories will remain opaque and enigmatic. Birckhead and Czerwinski recommended this collaborative approach proceed as soon as possible while the elders still survive. Unfortunately, the heritage funding was not extended beyond the desktop research stage.

This paucity of recognition of a significant aspect of Indigenous culture is indeed unfortunate. Silence about the rich mythology and power that standing stones hold is another in the long list where we have averted our gaze from the rich and deep cultural heritage of our own continent in favour of the ‘homeland’ our European ancestors left behind. It is just one among many silences that allow the ongoing misappropriations and misunderstandings to continue.

For many, the apparent absence of evidence signifies that the Aboriginal people were at contact nothing more than ‘savages’ passing through, as compared to the supposedly sophisticated civilising settlers – such as the proud Celts of Glenn Innes with their ‘unique’ standing stone heritage.

By Gib Wettenhall

4 October 2019

3,376 words

Knowledgeable elders still exist, says Dr Birckhead. “The old people I worked with have all been through the Law and know their part of the songlines and Dreaming tracts well. They sing these relationships in language, which is hard for non-initiated people to grasp.”

Living in towns on the coast, the elders seldom get back to Country. Substantial investment is required for extensive site visits, involving archaeologists and anthropologists, accompanied by cultural liaison officers as interpreters. Otherwise, each site’s totemic affiliations and creation stories will remain opaque and enigmatic. Birckhead and Czerwinski recommended this collaborative approach proceed as soon as possible while the elders still survive. Unfortunately, the heritage funding was not extended beyond the desktop research stage.

This paucity of recognition of a significant aspect of Indigenous culture is indeed unfortunate. Silence about the rich mythology and power that standing stones hold is another in the long list where we have averted our gaze from the rich and deep cultural heritage of our own continent in favour of the ‘homeland’ our European ancestors left behind. It is just one among many silences that allow the ongoing misappropriations and misunderstandings to continue.

For many, the apparent absence of evidence signifies that the Aboriginal people were at contact nothing more than ‘savages’ passing through, as compared to the supposedly sophisticated civilising settlers – such as the proud Celts of Glenn Innes with their ‘unique’ standing stone heritage.

By Gib Wettenhall

4 October 2019

3,376 words

|

|

em PRESS Publishing specialises in Australian landscapes and their historical and cultural contexts. em PRESS is particularly interested in fusing Indigenous, European settler and nature-based readings of the landscape to provide a truer view of our country.

|