Raising a green wood shed

The boat builder at Bulukumba.

The boat builder at Bulukumba.

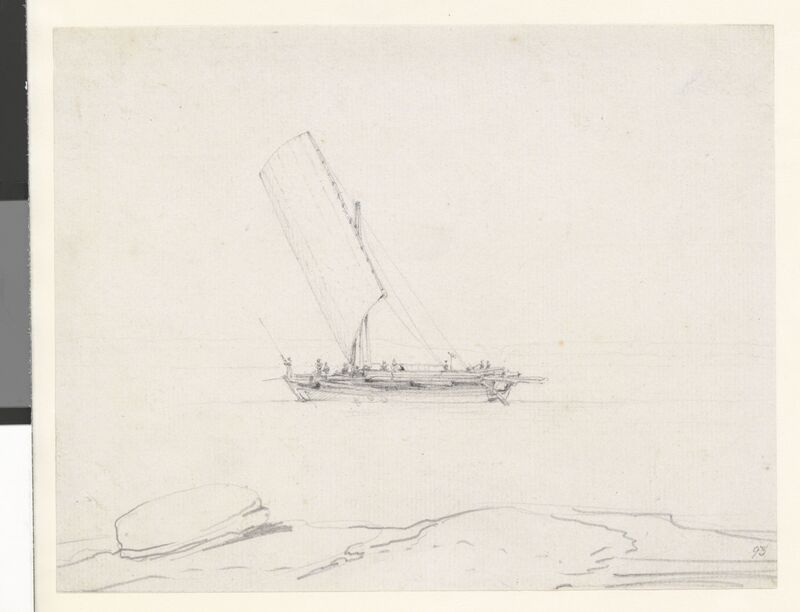

Last winter, I stood on the white sands of a remote tropical beach watching a Macassan man conducting the crafting of seven, teak-flanked phinisi boats, in much the same way they had been conceived for over a thousand years.

No plans on paper needed. The template, passed down from generation to generation, was inside his head. And his workers bantered amiably, as each of the seven ships of seven different sizes sprung into being from a well-grooved, familial structural form. Ships whose sails on the horizon had for centuries signalled for the Yolngu people of NE Arnhem Land the arrival of the Wet and trading opportunities for swapping trepang for tobacco. Ships whose ageless grace and function are now coveted globally as the epitome of authenticity.

In spring, I went with fellow farm foresters on a field trip to Victoria’s northern plains to see a splendid barn built the old English way, out of green wood. Not a plan, nail nor machine was in sight. Like the phinisi boats built on the beach at Bulukumba in Sulawesi.

No plans on paper needed. The template, passed down from generation to generation, was inside his head. And his workers bantered amiably, as each of the seven ships of seven different sizes sprung into being from a well-grooved, familial structural form. Ships whose sails on the horizon had for centuries signalled for the Yolngu people of NE Arnhem Land the arrival of the Wet and trading opportunities for swapping trepang for tobacco. Ships whose ageless grace and function are now coveted globally as the epitome of authenticity.

In spring, I went with fellow farm foresters on a field trip to Victoria’s northern plains to see a splendid barn built the old English way, out of green wood. Not a plan, nail nor machine was in sight. Like the phinisi boats built on the beach at Bulukumba in Sulawesi.

|

Once building with green wood was the norm not abnormal. Trees were felled, hewn with axe and adze, and a barn or boat of beauty rose nearby. The process made sense. Wood when green and dripping wet is ten times more workable than when hard and dried. Unlike nails, pegs joining post to beam and truss can cope with shrinkage. Only a few tools are necessary. A broad axe for hewing a log into a post or beam. A handsaw and chisel for fine detailing, such as carving beam ends to fit snugly into a rectangular slot on either side of a post’s top. An auger for drilling holes through post and beam for the wooden pegs. A drawknife for shaving pegs to a point while astride a saw horse. A hammer for knocking pegs into place, locking post and beam together.

Building with mortise (Old French for hole) and tenon (literally tongue) must have been based on natural principles, analogous, as it is, with the sockets and joints of animal bodies. Pegs replace muscles, fixing beams to posts firmly. Linked posts and beams appear similar to a row of people standing with their arms on their neighbours’ shoulders. The technique never caught on in Australia. Why? I suspect the Industrial Revolution disrupted tried and true traditional pathways. Mechanisation sped up processes, exponentially increasing milled timber volumes and profit potential. Axe and adze were vanquished by chainsaws and steam-powered saw benches. Moist and flexible green wood was abandoned in favour of the inanimate uniformity and rigid precision of kiln-dried wood. |

Each log was marked up for its particular place in the frame.

Each log was marked up for its particular place in the frame.

What if, I thought, I commissioned the young maker of the splendid barn to try his hand at reinventing the traditional Aussie-style farm shed, out of green wood? We would source the wood from my native forest on the edge of the Wombat Forest at the southern end of the Divide. We would choose for the mortise and tenon frame the common native hardwood, messmate, once described by the gold digger and explorer Alfred William Howitt as “the most useful” of trees; today, little used, displaced by that inferior Californian exotic, radiata pine. What could act as a more apt example of localism, reconnecting people to place, slowing the creative act down so it swung in tune with the planet’s beating heart?

Lachlan Park, the 28 year-old, fine wood craftsman, was keen. He and many of his fellow Millennials are sick of spewing out poorly-made, toxic stuff to serve the treadmill of economic growth. He wants to work with wood, not fight it, let alone lay waste to forests.

In the 1850s, over 570,00 immigrants arrived at the port of Melbourne, en route to the goldfields ‘up country.’ It was the greatest gold rush the world had ever seen. What also ensued was “a great slaughter of trees” as the region’s first forester, John La Gerche, confided to his journal. Much of the gold lay under the Wombat Forest; it was stripped bare and turned upside down. By 1897, a Royal Commission had declared the Wombat “a ruined forest.” Although it was to recover, the late 20th century innovation of clearfelling stripped the forest bare once more, reducing it to woodchips for papermaking.

Overcut, exhausted, the Wombat Forest was closed to clearfall at the turn of the 21st century. As happens when a forest is laid bare, thousands of seedlings germinated and strove for sunlight per hectare, replacing what were originally open woodlands with dense, even-aged thickets of eucalypt saplings.

This was the ‘young’ dark, impenetrable forest that greeted my family and I when we bought our 15ha block over 25 years ago. I took a Master TreeGrower course and learnt about the key silvicultural tool for breaking sapling gridlock in a regrowth forest – thinning. In the Wombat Forest, this has for many of us taken on the form of felling every second tree for firewood. By halving density, the remaining trees are released from fighting for their place in the sun. They gain space to survive and spread. And to our joy, the light let in has allowed the return of orchids and wildflowers, adding a pointillist palette to the bush at our back door.

Lachlan Park, the 28 year-old, fine wood craftsman, was keen. He and many of his fellow Millennials are sick of spewing out poorly-made, toxic stuff to serve the treadmill of economic growth. He wants to work with wood, not fight it, let alone lay waste to forests.

In the 1850s, over 570,00 immigrants arrived at the port of Melbourne, en route to the goldfields ‘up country.’ It was the greatest gold rush the world had ever seen. What also ensued was “a great slaughter of trees” as the region’s first forester, John La Gerche, confided to his journal. Much of the gold lay under the Wombat Forest; it was stripped bare and turned upside down. By 1897, a Royal Commission had declared the Wombat “a ruined forest.” Although it was to recover, the late 20th century innovation of clearfelling stripped the forest bare once more, reducing it to woodchips for papermaking.

Overcut, exhausted, the Wombat Forest was closed to clearfall at the turn of the 21st century. As happens when a forest is laid bare, thousands of seedlings germinated and strove for sunlight per hectare, replacing what were originally open woodlands with dense, even-aged thickets of eucalypt saplings.

This was the ‘young’ dark, impenetrable forest that greeted my family and I when we bought our 15ha block over 25 years ago. I took a Master TreeGrower course and learnt about the key silvicultural tool for breaking sapling gridlock in a regrowth forest – thinning. In the Wombat Forest, this has for many of us taken on the form of felling every second tree for firewood. By halving density, the remaining trees are released from fighting for their place in the sun. They gain space to survive and spread. And to our joy, the light let in has allowed the return of orchids and wildflowers, adding a pointillist palette to the bush at our back door.

A definite swing in the mobile milling.

A definite swing in the mobile milling.

Summer came and Lachlan and I began the green wood shed project by diverting some messmate thinnings from an ignoble fate as firewood. We selected 5m lengths of straight messmate from a firewood cutter and brought in a mobile bandsaw mill for shaping into post and beam. Except for rough bush affairs, eucalypts have fallen out of favour in shed building as they tend to shrink, spring and crack – unlike rigidly reliable steel framing. Of the eucalypts, messmate has one of the lowest shrinkage rates at 3%, compared to 6% for shining gum.

A friend found an old US Army manual online that showed Lachlan and his twin brother Joe how to pull the frame into place using a block and tackle on top of felled sapling cut to a length higher than the frame. Seated in a hole in the ground, the sapling is manoeuvred by ropes. This pre-industrial substitute for a crane is known as a gin pole and was easily capable of lifting 250kg, 200cm square tie-beams and 150cm square ridge beams. The wood size accommodates the surface splitting to which eucalypts are prone.

A friend found an old US Army manual online that showed Lachlan and his twin brother Joe how to pull the frame into place using a block and tackle on top of felled sapling cut to a length higher than the frame. Seated in a hole in the ground, the sapling is manoeuvred by ropes. This pre-industrial substitute for a crane is known as a gin pole and was easily capable of lifting 250kg, 200cm square tie-beams and 150cm square ridge beams. The wood size accommodates the surface splitting to which eucalypts are prone.

Where possible, we decided to use materially renewable resources, like timber. Stuff that was locally available and capable of recycling, for instance such as Baltic pine for flooring in the storeroom. Baltic pine came over by the shipload as ballast in the gold rush era and is now largely trashed when old houses are demolished around Ballarat.

Another choice was to avoid high embedded energy products, like concrete and steel. Combining these two constraints, we selected local sandstone for the foundations from Castlemaine; tracked down secondhand bricks for the posts’ piers; Lachie milled a wind-blown oak for the pegs; the roof was framed with green farm-grown cypress (it’s more stable than eucalypt timber); recycled rusty galvanised iron clads the roof and walls; and the vertical overlapping cladding for the store room was sourced from a local plantation of shining gum.

Another choice was to avoid high embedded energy products, like concrete and steel. Combining these two constraints, we selected local sandstone for the foundations from Castlemaine; tracked down secondhand bricks for the posts’ piers; Lachie milled a wind-blown oak for the pegs; the roof was framed with green farm-grown cypress (it’s more stable than eucalypt timber); recycled rusty galvanised iron clads the roof and walls; and the vertical overlapping cladding for the store room was sourced from a local plantation of shining gum.

|

The 9m X 5m gable-style shed has three equal-sized bays. The top two bays are open to the east, with their backs to the prevailing winds. One is for firewood, the other houses a small tractor. The third bay contains a storeroom that is insulated throughout and has double glazed windows. This makes it vermin-proof, cool and fit-for-purpose.

Once, the land, forests, rivers, seas and sky appeared endless. We know this viewpoint no longer holds true. But what are we doing to change direction from an ideological pathway of planetary plunder that heralds catastrophic global warming and the sixth wave of extinction? Despite what many people imagine, human history is not rationally ascending to some sort of Star Wars domination of the universe. Rather, we have made choices at crossover points in the past, like pursuing capitalism and mass production, which have had unintended consequences that are not necessarily proving benign. We stand in the middle of another crossover point. Many of the slow, place-based ways of the pre-industrial era are more suited to the rhythms of the earth. Like walking, wind power and eating the food that you grow, working with green wood connects people to nature, creating cultural artefacts of lasting strength and beauty. In our search for a more authentic and meaningful way of living, Lachlan and I like to think that rediscovering lost arts could contribute to bringing us back into balance. Putting theory into practice required patience, but it was to prove immensely satisfying. By Gib Wettenhall October, 2018 1,450 words This is a longer version of an article containing beautiful photos by Alison Pouliot. It was commissioned for the National Museum of Australia’s 'everyday future's' website |

|

|

em PRESS Publishing specialises in Australian landscapes and their historical and cultural contexts. em PRESS is particularly interested in fusing Indigenous, European settler and nature-based readings of the landscape to provide a truer view of our country.

|